VIOLIN FAQ: 20 Answers to Common New Violinist Questions

Getting started on any instrument is the hardest part. But the good news is that there are more resources freely available than ever for beginner violinists. The approaches to instruction are increasingly tailored to the student. And a good quality instrument may be researched online ahead of time, then found in stores and online faster than ever.

If you or your child are just getting started on violin, get acquainted with the parts of a violin, learn about choosing the right violin for a child. With the help of this guide, you’ll discover what the various tools should be considered for students starting out.

Here are answers to 20 commonly asked questions for violin beginners.

Table of Contents:

- What are the parts of a violin?

- What’s the difference between a violin and a fiddle?

- What size violin does my child need?

- What is the Suzuki Method?

- Where can I find free violin sheet music?

- What fingerings should I use for scales?

- How much should I practice?

- Do I have to use a shoulder rest?

- What type of shoulder rest should I use?

- What is the best type of metronome to get?

- What is rosin?

- What type of rosin should be used?

- What are the best strings for my violin?

- How often should violin strings be changed?

- What is the best chin rest?

- What edition of music should I use?

- What recordings are good to listen to?

- Do you have to be right handed to play violin?

- How do I keep my violin from falling out of tune?

- What is the best way to hold a violin?

![]()

1. What are the parts of a violin?

The sound box, featuring the famous f-shaped holes above and below the strings, is the main body of a violin. It is the ‘belly’ of the instrument because it is hollow and the source of the rich, pleasing sounds made when it is played. Woods like spruce are often used by luthiers—people who craft stringed instruments—and inside are a series of arches that bind and reinforce the body. A hard wood like maple is typically used for the arches.

The chin rest is the cup-like plate mounted on the bottom, front-facing side of the sound box. Some models also have a shoulder rest but they are not required, although a chin rest is standard.

From the bottom, the tailpiece also is mounted which is where the strings are anchored. Some violins feature 4 fine-tunings knobs on the tailpiece.

Just above the tailpiece, the bridge acts to raise, support, and hold the strings in place. It also spaces them apart. Bridges are not glued into place, and the first few times you string a violin, you will learn that there are techniques to get the bridge in place as the strings are tuned.

Just above the tailpiece, the bridge acts to raise, support, and hold the strings in place. It also spaces them apart. Bridges are not glued into place, and the first few times you string a violin, you will learn that there are techniques to get the bridge in place as the strings are tuned.

The f-holes on either side of the bridge emit the sound of the violin from out of the sound box.

The top-side of the long neck of the violin is the fingerboard. Some call it the fretboard, but that is a term for other stringed instruments, like guitars; violinists term it the fingerboard.

Above the fingerboard are 4 pegs. These are used to wind the strings and hold them in tune. Unlike guitars, which have tuners that feature machined parts and pieces, the pegs of a violin simply fit into the holes and are gently tapped into place.

Lastly, the top of the violin is called the scroll. Thought to be merely ornamental—and they are attractive carvings—they can serve to hook the violin when it is not being played.

2. What’s the difference between a violin and a fiddle?

Classical players call their violins a “fiddle” to be affectionate. In the U.S., a fiddle is not so much a different instrument as it is a different style of playing. Fiddling has its roots in Irish, Scottish, and French traditional music that have descended into bluegrass, Appalachian, Cajun, and other styles.

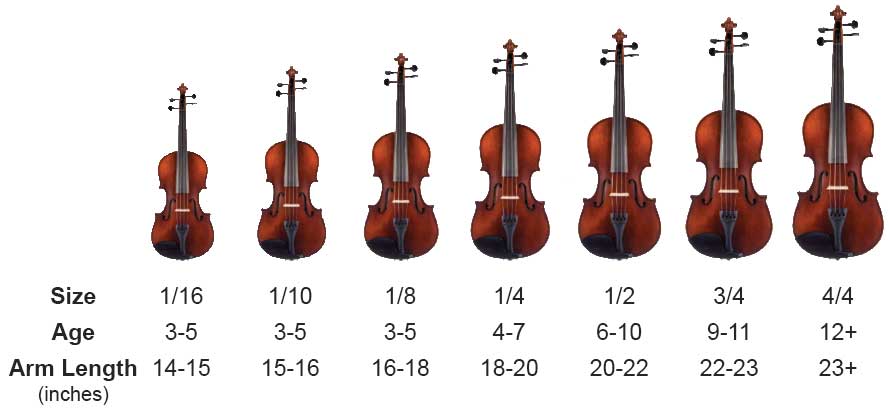

3. What size violin does my child need?

There are about 9 different sizes of violins for players from one-year old to adult. It is not so much the child’s age as it is the length of his or her arms. Best bet is to consult with the instructor because some have opinions—in addition to a lot of experience—as to what size violin to start with.

Briefly, here’s some basics:

- Age 11+ with 23”+ arm length: 4/4 or Full Size

- Small teen or adult, 22” or less arm, small hands: 7/8

- Age 9-12 with 21.5”-22”: 3/4

Younger than 9 with arms shorter than 21”, the sizes descend based on age and about 1-1.5” in arm length as follows: 1/8, 1/10, 1/16, and then 1/32, which would be for little tykes having arms less than 14” long.

4. What is the Suzuki Method?

The Suzuki method is a way of going about teaching, and it was developed in the mid-20th century by a Japanese pedagogue who happened to be a violist, named Shinichi Suzuki. Born in 1898, Suzuki lived 100 years—long enough to have seen his approach to teaching and curriculum for music adapted internationally. He was inspired following WWII in efforts to rebuild Japan.

Suzuki’s philosophy is that children can learn an instrument much the way they learn their native language: small steps, one thing at a time. So, by using a kind of linguistic approach and making the learning of the violin and music “bite sized,” as we might say today,” very young child could participate and gain meaningful skills at a very early age.

Many people equate violin instruction and terms like Suzuki to mean a child can be a prodigy. Quite the opposite, Suzuki’s mission was to help foster in children “noble hearts.”

Suzuki once famously said, “I want to make good citizens.

5. Where can I find free violin sheet music?

Honestly, if you search online, there is all kinds of free sheet music. Much of the classical music and common folk songs are in the public domain, so you’re not doing anything wrong by visiting those sites.

You can find Pachelbel’s Canon in D, Bach’s Concerto for Two Violins in D minor, Schubert’s Andante for Trio Sonata Op. 99, and so on. The real question is how and when the beginning violinist will be ready to tackle some of this music.

6. What fingerings should I use for scales?

As the player gets going, learns to read notes, and so forth, there are loads of free sheet music. If an instructor is not being used, one place to visit is https://www.pinterest.com/pin/534028468296173436/. There you will find major and minor scales, and even very simple illustration for newbies to visualize per finger on the fingerboard how to get started on scales.

7. How much should I practice?

The great Leopold Auer was once asked this question. Auer responded: “Practice with your fingers and you need all day. Practice with your mind and you will do as much in 1-1/2 hours.” Many will tell you that practicing more than 4 hours in any one day means you’re not doing it right—and you need to let the mind and body rest, to internalize what worked and what did not, and to let muscle memory take root.

8. Do I have to use a shoulder rest?

Violinists still debate this, but the bottom line is you do not need a shoulder rest to play the violin. What is it? It is like a padded bar attached to the back of the body, meant to support the instrument over the should of the players.

9. What type of shoulder rest should I use?

There are many on the market, so when it comes to shoulder rests, it may be best to go to a music store or seek input from the instructor—if they even want the student to have one. Here is an article that may be more helpful: http://consordini.com/best-violin-shoulder-rests/

10. What is the best type of metronome to get?

Metronomes are tools used to keep time while you are practicing. An infinite variety of options are out there. Some are electronic and have drum patterns. Others are the simplest, old-fashioned variety requiring no batteries; you wide them up and they tick-tock away. What you choose is a matter of budget and what the student will find engaging and effective. They can cost as little as $10 or $20 and as much as $125 or more.

For beginners, start with something relatively simple and low cost. Digital products are likely best for today’s learners. You put in a battery, don’t need to worry about winding and re-winding them, and they have at least a few varieties of sounds or beats.

11. What is rosin?

Rosin is used for bowed, string instruments in the form of cakes or blocks. These are used on bow hair so the bow’s strings have increased friction—they can grip the strings and make them vibrate more clearly.

12. What type of rosin should be used?

Here again, there are so many brands and varieties, over time you will narrow down what is preferred. Generally, the darker the color, the softer and stickier; and, the lighter, the less so. A harder-feeling rosin is easier to clean than sticker ones, because it isn’t as powdery. But the sound is not as good as the darker, softer rosins. So, you will want to explore how much the sound matters, the feel of the bow in terms of the level of friction, and the factor of cleaning up of the instrument.

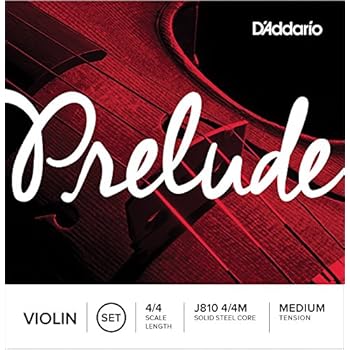

13. What are the best strings for my violin?

There are many on the market. Often, lower cost beginner violins come with lower grade strings. Poor strings—and poor stringing of the violin—lead to frustration and disappointment out of the gates. Not wanting to endorse any one brand, it is noted that D’Addario Prelude Violin Strings are very commonly used. If you research that set and those that pop-up along with them, you are zero-ing in on strings that walk the line between a nice sound and greater playability.

14. How often should violin strings be changed?

Well, here, the laws of use and disuse are at play. The more you play the violin, the more you may sense that the resonance is not as full as it once was. Or, you may even see some wear and tear, or wearing down on common positions of strings on the fingerboard.

As a rule of thumb, perhaps put into your cell phone calendar to change strings every 3 to 6 months as a habit. Early in the career of the new player, it is just too hard for you or for them to tell when it is time. So, entering a repeating “appointment” to change strings, say, every 4 months keeps the instrument on the top of its game.

15. What is the best chin rest?

Frisch, a Virginia-based violin maker, has this to say: “There’s this idea that by clenching the instrument, the left hand is freer for better shifting and for producing vibrato. It seems logical, but most people with really good vibratos have told us, ‘No, you really have to have your shoulder free.’”

Some teachers have a traditional notion that a good chin rest is one whereby the player can clench the violin in position without aide of the fingering hand. Well, more recent thoughts are that a design that may be a bit more open—less of a deep cup, less sharp contouring—can lead to healthier postures and variations in the shoulders, reducing fatigue and enabling better vibrato.

16. What edition of music should I use?

Despite ambitions to jump right into Bach, there are old standards, tied-and-true, that beginners will recognize and find simpler to learn. Here’s just a few examples to give you the idea:

- “Mary Had a Little Lamb”

- “Hot Cross Buns (round)”

- “Go Tell Aunt Rhody”

- “Frère Jacques” (Brother John – round)

- “Row, Row, Row Your Boat” (round)”

- “Have You Seen the Ghost of John” (round)

- “London Bridge is Falling Down”

17. What recordings are good to listen to?

Without a doubt, playing violin music in the home, even as background to homework or dinner, can attune the beginner to familiarity and appreciate for the wonderful sounds and dynamic ranges of music they could enjoy and eventually learn to play. Pick what you like at first and let the player also explore your collection or an online radio channel that randomly plays violin-based solos and ensembles.

Also, as painful as it may sound in the beginning, recording a practice now and then is helpful. The learner comes to understand it is not a critical exercise and that listening to how he or she really sounds is a constructive way to say, “Oh, yeah, that note really needs some work.”

It is not constructive to berate and incessantly point out each and everything that was wrong—anymore than it is to pretend the practice sounded perfect. The goal is to develop good habits of listening skills, so the student can learn from their own strengths and opportunities to improve.

18. Do you have to be right handed to play violin?

Nope. There are instruments designed or configured for left-handed players.

19. How do I keep my violin from falling out of tune?

First, properly stringing the instrument is important. Perhaps bring it into a store or find a friend who knows how it is done the right way. Watch them and learn; there are little tricks to stringing violins, dealing with the unglued bridge, and getting the pegs set into place firmly.

The peg, by far, is the most important element. The wedge effect of the peg, which is narrow at one end and grows gradually fatter, is what keeps strings in tune. Humidity can affect the pegs and the scroll, because wood reacts to humidity. That alone can “untune” the violin. So, learning to wedge the pegs more and more firmly into the holes, as the tuning reaches the right pitch, is the art of tuning.

20. What is the best way to hold a violin?

For the left, or playing hand:

- You elbow remains under the center of the violin.

- Your wrist is gently rounded.

- Avoid resting your wrist on the neck of the violin.

- Your thumb is kept opposite the first or second finger.

- Create a curved, backwards C-shape in the open space between the thumb and index finger.

![]()

![]()

The posture should be standing, feet shoulder width apart, and your knees relaxed—not locked nervously into place. Perhaps put the left foot slightly forward.

When playing seated, use the chair as your base to sit straight. Some players lean forward to keep a straight back without as much weight on the spine, and place the left foot slightly forward for balance and reducing engagement of the thighs—which just adds up over time to fatigue and tension.

Leave a Reply